Rama not only strings the bow, he breaks it. Viswamithra asks if Rama can attempt to string the bow. When he sees Rama, Janaka laments that Rama can't marry his daughter, Sita: he set the condition that a suitor must be able to lift and string Shiva's bow, a massive bow once owned by the god.

She spends the night moving from bed to bed, trying to get comfortable. The woman, Sita, sees Rama as well and is immediately overcome with love for him. When they enter the city, Rama sees a beautiful young woman on a balcony. Viswamithra then takes the boys to Mithila City.

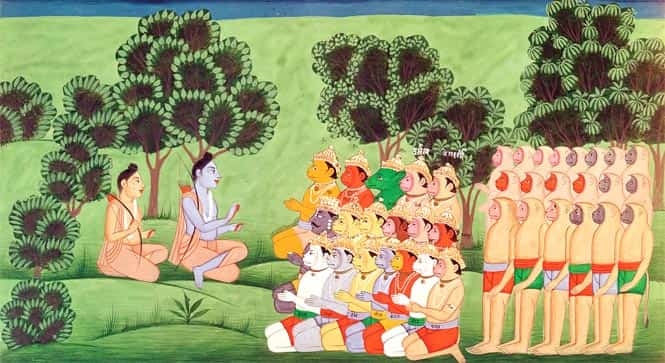

Rama assures the sages and saints of their safety as they begin the sacrifice, and he shoots the gathered demons with his bow. Viswamithra tells the boys several more stories before they reach the site of the sacrifice. Rama does, and the gods ask Viswamithra to teach Rama about weapons. Thataka appears and threatens to eat the travelers, but Viswamithra instructs Rama to kill her. As Viswamithra travels with the boys, he tells them the story of a demoness named Thataka. Dasaratha is heartbroken, but agrees, and sends Lakshmana with Rama. One day, the sage Viswamithra comes to Dasaratha and asks that Rama accompany him to protect him during a sacrifice. Kausalya has Rama, Kaikeyi has Bharatha, and Sumithra has the twins Lakshmana and Sathrugna. When the sacrifice is complete, Dasaratha's three wives bear sons. The messenger tells Dasaratha to call a specific sage to conduct a sacrifice. Vishnu agreed to incarnate as a human to defeat Ravana. His mentor remembers a vision in which the gods appealed to Vishnu to help them defeat Ravana, a demon who uses his powers for evil. RamayanaR.K.Dasaratha, king of Kosala, is childless and desperately wants a son to succeed him as king. It can be enjoyed and appreciated, he suggests, for its psychological insight, its spiritual depth and its practical wisdom—or just as a thrilling tale of abduction, battle and courtship played out in a universe thronged with heroes, deities and demons. Here, drawing his inspiration from the work of an eleventh-century Tamil poet called Kamban, Narayan has used the talents of a master novelist to recreate the excitement and joy he has found in the original. Every child is told the story at bedtime… The Ramayana pervades our cultural life.’ Although the Sanskrit original was composed by Valmiki, probably around the 4th century BC, poets have produced countless variant versions in different languages. Everyone of whatever age, outlook, education or station in life knows the essential part of the epic and adores the main figures in it—Rama and Sita. Narayan in the Introduction to this new interpretation, ‘is aware of the story of The Ramayana. ‘Almost every individual living in India,’ writes R. The Ramayana is, quite simply, the greatest of Indian epics—and one of the world’s supreme masterpieces of storytelling. A shortened modern prose version of the Indian epic.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)